Maiolica Misconceptions

Italian 17th Century Drug Jar

I say popular because out of the many ceramic decorative techniques that have been done over the centuries, this is still being widely done worldwide, and it carries a pretty hefty price tag by the talented artist. It’s also reasonably easy to reproduce. Many hobby shops and do-it yourself ceramic stores like “Color me Mine” chains have hobby equivalent kits and samples of the white base glaze with the multi-colored paints (glazes) to use on top of it in order to fake the original look. In addition, there are still potteries (towns) in existence that have been making this same pottery for over 800 years which says a lot about the demand of the art as well as the strong tradition.

Her questions were: “Why didn’t our medieval cousins in Spain or Italy just use porcelain which was all white instead of using a white underglaze across the less than lovely earthenware? And why do both sides instead of one side? And Maiolica is only Italian, isn’t it? It never came into Spain, nor did other countries like Spain have such lovely wares like Maiolica.”

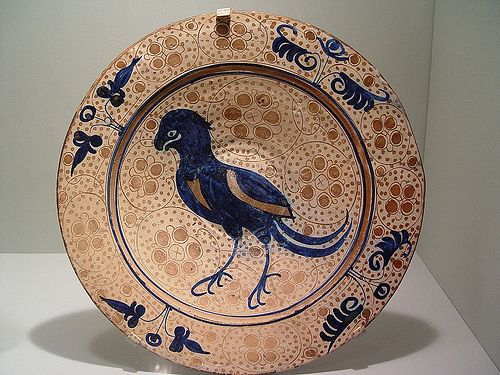

Dish with Bird, Hispano Moresque 15th Century

>whew< Lots of questions. Here are the answers: I think the best approach is explaining what is Maiolica and all the rest of the questions (misconceptions) will be answered. Maiolica is another name for Tin-glazed pottery or earthenware. There are actually several names for Tin-glazed pottery depending on the origin of the pieces. Tin-glazed pottery is pottery covered in glaze containing tin oxide, which is white, shiny and opaque. (See tin glazing.) The pottery body is usually made of red or buff colored earthenware and the white glaze was often used to imitate Chinese porcelain. Oxides or colorants are used across the base glaze in order to decorate the piece and the glaze and oxides melt together in the kiln. The other names for Tin-glazed pottery can be Hispano-Moresque Ware (Spain), Delftware (Netherlands & England), Faience (French), Maiolica (Italy and very general term used modernly for the technique), and Majolica (a term that has seeped into ceramic consciousness from the 18th Century). The technique came through Moorish potters originally and was named for the trading island on the trade route called Majorca (at least one of the stories for the name is). Through Majorca the wares went to Spain, then to Valencia and finally to Italy.

With this being said… per the Victoria and Albert Museum: “The term 'maiolica' was used in 15th-century Italy for lustrewares imported from Spain. It is usually said that the name derives from Majorca, an island that played an important part in this trade. But it has recently been argued that the name derives from 'obra de Mallequa', the term for lustred made in Valencia under the influence of Moorish craftsmen from Malaga. The name was soon adopted for Italian-made lustre pottery copying Spanish examples, and during the 16th century its meaning shifted to include all tin-glazed earthenware.” (Website over here.

Lusterware, Hispano Moresque 15th Century

Tin-Glazed wares were invented because of the popularity of China porcelain, especially the blue on white pieces (which are still being produced in China and other Asian countries). In most of Europe, the potters didn’t have access to porcelain or any sort of clay that was remotely that white, smooth or reflective. Also they didn’t have the know how to get their kilns hot enough to fire porcelain to the correct temperatures for vitrification. Chinese porcelain was highly sought after and it was very popular with the rich and well to do. So, as a potter trying to make a living, they tried for years to come up with a way to recreate porcelain using what they had on hand. The earliest samples of tin glazed pottery have been found in Iraq in the 9th Century.

So, for a potter to hit it big time and get more commissions, they would want to try to conceal their red or buff clays with some sort of white glaze, then decorate it with oxides (colorants) to make their pieces look as close to the porcelain as possible. If you left one side unglazed, then the whole faux finish was lost.

Delftware, Jar with William of Orange on it

Pottery, however, is far from easy. It is definitely part art and very much the science of chemistry. There are basics when creating a glaze, since all glazes have a glass element, a melter (something that melts the glass-glaze element), and a stabilizer (something that keeps the glaze from running off the piece and together) within them. You have to worry about textures (smooth or rough… and there are tons of variants in between), the opacity (is it a clear glaze or opaque, again variants within), and then one of the biggest factors of all, which is, how the glaze “fits” on your clay body.

What “fits” is that when you glaze your pieces, will the glaze be what you envisioned it to be or will there be glaze faults. There are numerous glaze faults, each one needing troubleshooting through a series of chemical adjustments, application variation and changing up firing (one list of glaze faults and how to fix them is here. A few of the common glaze faults can be crackling, pin holing, blistering, running, and crawling. With tin glazed pottery, one of the issues the potters were having was a glaze fault called “shivering” which was when the glaze was literally falling off the pot either right after firing, or later. Shivering is when the glaze compresses too much and pops completely off, or that it squeezes the clay body so much that it cracks off.

Italian Drug Jar, 17th Century, Maiolica

Being that this was such a popular technique once the secret was out on how to make it, most European countries have a version of it. They just don’t always call it by the same term as “maiolica” (see above for the various terms). More recently, as the archeologists were digging up tombs in Egypt, they came across very bright blue pottery and thought it was tin glazed work, so they called it “faience.” This is actually not the same at all, but what we potters call Egyptian paste, used for beads and smaller decorative items. It is a clay body that has the glaze mixed within it, so when it fires, the turquoise glaze develops across it’s surface.

Being that we live in such a modern age, with airplanes and the ability to pretty much get whatever we need as artists, many of us forget that it wasn’t always like this. For potters in Europe, they worked with what they had and developed over time new techniques. That’s the great thing about history, seeing where it all started and how far along we came, even if it’s only a piece of pottery.

Italian Drug Jar, 17th Century Maiolica

Labels: hispano moresque, maiolica